By Randall H. Reid, Southeast Regional Director/Director of Performance Analytics, ICMA

“Originally published in Government Finance Review, February 2016, www.gfoa.org.”

In this article, ICMA Director of Performance Initiatives Randall Reid reinforces the importance of partnership between local government chief administrators and chief financial officers to lead a renewed, systematic focus on organizational performance. Comparison and benchmarking, assisted by new analytics platforms, are key components of this focus.

The basic principles of performance management – such as efficiency and effectiveness of service delivery, the importance of measurement, and the value of benchmarking and comparing with peers – have endured. At the same time, dissatisfaction levels with state and federal government are high, and citizens tend not to see officials in these levels of government as effective problem solvers. In this environment, the solutions to many of the nation’s problems increasingly reside at the local level, where public officials must focus intensely on accountability, performance, transparency, and the engagement of residents in decision making to maintain the unique credibility that local government still enjoys.

Frankly, performance does matter, and when the chief executive and chief financial officer agree to support performance management systems, the process prospers and can be best implemented throughout the enterprise to harness the power of analytical platforms. This is why the International City/County Management Association (ICMA) Center for Performance Analytics is creating a national database of performance management metrics for the benefit of all local governments.

The reasons for this undertaking remain the same today as they were ICMA began its work in the area in the 1930s. Performance management is intended to inform better decision making. It also empowers:

- Performance reporting to elected officials and citizens.

- Budget preparation and resource allocation.

- Better management and direction of operational units.

- Baseline information for process reengineering and testing new procedures.

- Developing scopes of work and monitoring contracts.

- Supporting planning and budgeting systems.

- Program evaluation and resource realignment.

- Benchmarking with comparable jurisdictions to determine best practices.

- Providing meaning, scale, and context to staff reports and recommendations.

DEFINING PERFORMANCE

Without performance management, governments do not truly know how well they are performing. They lack a means of defining, communicating, and measuring their success. Performance management can, for instance, help jurisdictions see why others get better results with similar resources. In addition, the growth of open databases and the analytical tools available to citizens have increased the risk that performance data reported to other organizations will be mined and reported by reporters, bloggers, or others, increasing the risk that a government will be caught unaware and lose credibility.

One author[i] describes this point in time as “the intersection of more to know, more tools to help us know, and the expectations that we will do something with what we know.” It is no accident that a fast-growing field of journalism is the exploration of public records and open data sources to seek out and report on failures, creating or worsening administrative credibility with a jurisdictions’ own information. Few organizations can afford to have its critics or a hostile news media define its performance and reputation unjustly.

An Act of Management

In many jurisdictions, the administrative tasks and the management capital required to mandate the enterprise-wide collection of performance data remains challenging in the face of passive or direct staff resistance, lack of legislative focus on the benefits for taxpayers, and legacy software or spreadsheet technology. The “will” to maintain the process also frequently wanes over time with staff changes. If the performance management process is not institutionalized, staff may come to view it as a fad, thinking “this too shall pass.” It must therefore become a prevailing practice.

As David Ammons wrote recently: “In contrast to a set of performance measures, performance management is not a tool, it is an act – an act of management. Managers at various levels of an organization can choose to engage in the act of performance management. When they do so, their actions begin with observing the current state of performance, proceed to committing to the pursuit of a more favorable level of performance, and culminate in taking steps to achieve the targeted level. Only by reaching the third step do managers engage in performance management.”[ii] His key point: “Those who see performance management as a system of channeling performance information to the top of the organization for centralized decision making are misreading what actually happens when performance management works.”

Leaders are responsible for ensuring positive results and high-quality government programs or outcomes for citizens. Any renewed focus on performance will therefore require government leaders to create an institutionalized performance culture that can survive transitions in administrations and that do not depend solely on the charisma of an executive. Studies of programs like CitiStat, Baltimore’s performance management initiative, find that when a chief executive expresses regular interest in specific performance results and top executives have periodic meetings with agency heads that focus on program metrics, program-level staff have more of an incentive to practice performance management themselves.

Performance data are vital to the daily operational decisions of supervisors. Line department managers should include data analysis in their recommendations. Daily accounting and monitoring activities to support the system deep within the organization help policymakers make decisions and implement programs smoothly. Performance metrics should lead to greater operational awareness for staff and executives, while analytics should allow managers to understand and use the data for decision making and insights into potential improvements.

The Era of Analytics and Data-Enhanced Decision Making

The role of technology has changed over the years, and analytics is now the best way to approach performance management. It makes sense to embrace technology-enhanced platforms to handle the magnitude of data generated not only by current software but through the “smart devices” and remote sensors that are transforming our transportation and utility grid systems.

The era of big data has ushered in an age where the collection of data and its use in cities to make more informed decisions is made increasingly easy through analytics platforms like the ICMA Insights platform, which allows communities to enter, clean, report, benchmark, and analyze their data. Future performance platforms must blend fiscal management and operational intelligence to create the strongest analytical solutions for governmental managers.

Big Data Terminology Alienates Many Local Governments

Two Kinds of SMART Performance

Most of us are aware of the old acronym SMART for developing performance measures or objectives – they should be specific, measureable, achievable, relevant, and timely. That remains true, but now a second SMART acronym reflecting the five steps of performance-based analytics:[iii]

S – Start with strategy (How will I implement this effort and what am I seeking to accomplish?).

M – Measure metrics and data (How and with what and do I measure performance?).

A – Apply analytics (How will our analytics platform be used to gain insight into data I have?).

R – Report results (How can I share this insight with stakeholders?).

T – Transform city or county operations (How do we continuously improve our organization to achieve its mission?).

The Value of a Comparative National Database

Know thyself. Organizational knowledge is the most valuable component of operational improvement. Unfortunately, performance management is often used solely for self-awareness and internal business intelligence. Many managers and budget officers wish to keep performance information to themselves, considering their jurisdictions unique and perhaps believing that no “local government service industry” metrics really apply to their communities. Occasionally they turn to their peers when they need for comparative metrics (often to defend their assumptions about their operational performance), but such ad hoc inquiries are likely to produce ill-defined metrics and apples-to-oranges comparisons.

This is equivalent to bowling, swimming, or golfing alone. While you can practice and even improve by keeping score or by recording personal best times just for yourself, you lose the opportunity for camaraderie, knowledge exchange, and the incentive for improvement that comparing or competing provides.

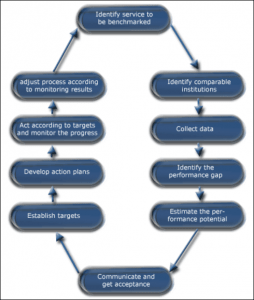

Benchmarking is the process by which an organization captures specific data related to its costs and performance—that is, the baseline, or current state—and then evaluates the cost and performance data against those from one or more other organizations. (See Exhibit 1 for a map of the benchmarking process.) Benchmarking your own operations is vital for making informed decisions, undertaking continuous improvement efforts, and developing a common language for collaboration with others for service delivery or contracting.

Although many factors affect financial performance, it can be instructive to see how your city or county compares with others on such measures as per capita expenditures for fire/emergency medical services, road rehabilitation, code enforcement, and other public services; or on revenue measures such as net recycling revenue per account. Just as important, the descriptive data ICMA collects allow Insights users to filter data according to policy, demographic or operational considerations, such as the use of paid-on-call/volunteer firefighters, days of snow or freezing conditions, methods of community-oriented policing, median income, percentage of the local population with a college degree, or even whether certain internal services are centralized or decentralized. Comparisons of this kind can lead to discovery of successful management practices in other local governments that can be adopted locally to improve financial performance.

The ICMA Center for Performance Analytics works with consortia of communities that seek to benchmark their performance against their peers – collecting metrics that will help them expand the knowledge base of local government performance and identify best practices. Consortia may be based on geography or on functional areas, such as college communities, ski towns, or port cities. ICMA has been in contact with national associations such as the Government Finance Officers Association and with state associations, universities, and regional councils of governments to further this collaboration, and it welcomes such alliances in the future.

ICMA Insights is designed to encourage and facilitate benchmarking because it provides our greatest opportunity to gather uniform metrics about local government performance and enable users to identify appropriate communities with comparable demographics, community attributes, or specific facilities to encourage benchmarking, generate research, and identify best practices for all local governments.

Exhibit 1: The Benchmarking Process

[i] Thornton May, The New Know: Innovation Powered by Analytics (Wiley, 2009).

[ii] David Ammons, “Getting Real About Performance Management,” Public Management, December 2015.

[iii] Developed by Bernard Marr, chief executive officer of Advanced Performance Institute and author of Big Data (Wiley, 2015).